By David Hoffman Washington Post Foreign Service Sunday, January 30, 2000

By David Hoffman Washington Post Foreign Service Sunday, January 30, 2000

DRESDEN, Germany – In the gray villa at No. 4 Angelikastrasse here, perched on a hill overlooking the Elbe River, a young major in the Soviet secret police spent the last half of the 1980s recruiting people to spy on the West.

Vladimir Putin looked for East Germans who had a plausible reason to travel abroad, such as professors, journalists, scientists and technicians, for whom there were acceptable “legends,” or cover stories.

CLICK IMAGE for direct link to story.

The legend was often a business trip, during which the agents could covertly link up with other spies permanently stationed in the West. According to German intelligence specialists who described Putin’s task, the goal was stealing Western technology or NATO secrets. A newly revealed document shows Putin was trying to recruit agents to be trained in “wireless communications.” But for what purpose is not clear.

Putin defends the Soviet-era intelligence service to this day. In recent comments to a writers’ group in Moscow, he even seemed to excuse its role in dictator Joseph Stalin’s brutal purges, saying it would be “insincere” for him to assail the agency where he worked for so many years. Fiercely patriotic, Putin once said he could not read a book by a Soviet defector because “I don’t read books by people who have betrayed the Motherland.”

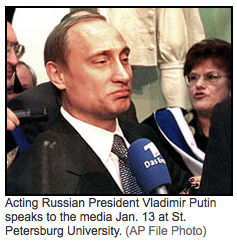

Such is the professional background of the man who emerged unexpectedly last month as Russia’s new leader. Today, Putin is acting president and the clear favorite to win the March 26 election and a four-year presidential term. Yet a review of his career shows that Putin previously has thrived in closed worlds, first as an intelligence agent and later in city government.

Until he was handpicked in August by then-President Boris Yeltsin to become prime minister, Putin had never been a public figure. He spent 17 years as a mid-level agent in the Soviet KGB’s foreign intelligence wing, rising only to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Later, as an aide to a prickly, controversial mayor of St. Petersburg, Russia’s second-largest city and Putin’s home town, he made a point of staying in the background.

Yet Putin’s career also suggests that he witnessed firsthand the momentous finale of the Cold War. From the front line in East Germany, Putin saw how the centrally planned economies of the East staggered to disintegration. In St. Petersburg, he had a taste of the ragged path of Russia’s early transition to a free-market, democratic system.

What Putin has taken from these experiences is not entirely clear. He has embraced the conviction that “there is no alternative” to market democracy, and soberly acknowledged Russia’s economic weaknesses. But he also has expressed enthusiasm for reasserting the role of a strong state. He has said the Russian economy has become “criminalized,” but so far only hinted that he would tackle the powerful tycoons who lord over it. Putin has vowed Russia will not revert to totalitarianism, but he has not demonstrated much skill working with Russia’s fledgling, competitive political system.

Putin has never campaigned for office, and he told an interviewer two years ago he found campaigns distasteful. “One has to be insincere and promise something which you cannot fulfill,” he said. “So you either have to be a fool who does not understand what you are promising, or deliberately be lying.”

Stasi and ‘the Friends’

Putin, an only son, was born in Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, to a factory foreman and his wife in 1952, shortly before Stalin’s death. He entered Leningrad State University’s law department in 1970, but the Soviet Union was not a state governed by the rule of law. Valery Musin, then a university lecturer, said the law department was a training ground for the KGB, the police and the bureaucracy.

Putin later recalled that the KGB targeted him for recruitment even before he graduated in 1975. “You know, I even wanted it,” he said of joining the KGB. “I was driven by high motives. I thought I would be able to use my skills to the best for society.”

After a few years spying on foreigners in Leningrad, Putin was summoned to Moscow in the early 1980s to attend the elite foreign intelligence training institute, and then was assigned to East Germany. He arrived in Dresden at age 32 when East Germany was a major focus of Moscow’s attention. The German Democratic Republic was home to 380,000 Soviet troops and Soviet intermediate-range missiles. Berlin was a constant source of Cold War tensions and intrigue.

At the time, several thousand KGB officers reported to a headquarters at Karlshorst, outside Berlin; Soviet military intelligence also was stationed in East Germany. But the biggest intelligence operation was the East German secret police, the Stasi, who monitored hundreds of thousands of citizens and kept millions of documents on file.

The broad Stasi network was used often by the KGB, and the raw intelligence sent directly to Moscow. The East German dictatorship, headed in those years by Erich Honecker, remained steadfastly rigid even as Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was beginning to experiment with political and economic reforms at home.

In Dresden, the KGB outpost at No. 4 Angelikastrasse was located directly across the street from the city’s main Stasi headquarters. The Stasi poked into every aspect of life; in Dresden alone, the documents they preserved on citizens now stretch nearly seven miles in the archives here, according to Konrad Felber, a spokesman for the commission that maintains the documents.

There is little information about Putin’s specific tasks in Dresden, but specialists and documents point to several assignments, including recruiting and preparing agents. The work likely involved Robotron, a Dresden-based electronics conglomerate, which was the Eastern Bloc’s largest mainframe computer maker and a microchip research center.

At the time, a major KGB effort was underway to steal Western technology. The Soviet Bloc was so far behind, according to a German specialist, that agents at Stasi headquarters often preferred to work on a Western-made Commodore personal computer rather than on their office mainframe.

The presence of Robotron may have provided Putin with legends for sending technicians to the West, or for recruiting Westerners who came to East Germany from such large electronics companies as Siemans or IBM. Putin may also have been interested in military electronics and intelligence about NATO from informers in the West.

The KGB was known to the Stasi as “the friends,” and it relied on the Stasi for support. For years, the Stasi prepared fake passports and driver’s licenses for “the friends” to create cover stories for agents. Tens of thousands of people in East Germany were “registered,” or marked in the secret files of the Stasi, as being “of interest” to the KGB. According to the German specialist, some were marked because the KGB was searching for people with plausible cover stories for trips abroad.

“You needed a guy with a background that looked good, a professor who had to go to an international conference or had to do business in the West,” he said. “You needed such a legend.”

Later, Erich Mielke, the East German state security minister, tried to rein in the Stasi’s assistance to the KGB, which led to one case in which Putin is known to have been involved. On March 29, 1989, Maj. Gen. Horst Bohm, then the head of the Dresden branch of the Stasi, wrote a memo to Putin’s boss, Gen. Vladimir Shirokov. While some names in the letter are blacked out, sources said the case involved Putin.

Bohm complained the KGB was recruiting reservists from the East German military who had gone into civilian life. They were being recruited “frequently” for temporary, special missions, Bohm said.

One reservist was called in, he said, to the Dresden “recruitment center” and was sent to talk with two Soviet civilians. “These talks included the issue of special training for wireless communications and also a short mission once each quarter of the year,” the letter says. But Bohm complained that the agent was already working for the Stasi and urged the KGB to keep its hands off. “It is not possible” to recruit the East German army reservists for wireless communications training, he insisted.

Bohm later committed suicide, but one of his aides, Horst Jemlich, said in a brief telephone interview that the KGB was interested in procuring Western technology.

A puzzling and unexplained aspect of the Bohm letter is a reference to Soviet “military intelligence,” which was a different agency from the KGB, to which Putin belonged. It is possible Putin was targeting Western military operations.

Putin also turned to the Stasi for help with routine logistics, such as obtaining a telephone – they were strictly controlled – and apartments. Putin was formally assigned to run a Soviet-German “friendship house” in Leipzig and carried out the duties, but this apparently was his own cover story. Intelligence specialists and political scientists said Putin may have had a political assignment to make contact with East Germans who were sympathetic to Gorbachev, such as the Dresden party leader Hans Modrow, in case the Honecker regime collapsed.

Putin’s work with the Stasi won him a bronze medal in November 1987 from the East German security service, but the reasons for the award are unknown. It was described by one source as the next level up from the lowest, basic award for service.

Clearly, Putin was on the seam of East-West confrontation at the end of the Cold War, and the lessons were self-evident. In East Germany, Putin “must have noticed the system did not work anymore,” said the German specialist. “If he was not stupid he would have noticed the East Germans were the losers of economic history.”

The Soviet economy was also in trouble. Yuri Andropov, the KGB boss and later Soviet leader, had responded in the early 1980s by trying to impose more discipline on the ailing system, and many in the KGB shared his hope it could be saved from within. Others thought this to be unrealistic and believed the system itself would have to be junked. Putin, in a newspaper interview last year, hinted that he believed the system could have been salvaged. He said that “few people understand the magnitude of the catastrophe that happened late in the 1980s when the Communist Party had failed to modernize the Soviet Union.”

‘In the Farthest Corner’

When Putin returned to St. Petersburg, he took a job for a year and a half as assistant to the rector of the university, dealing with “international relations.” However, that was partly a cover story. He was still working for the KGB, recruiting or spying on students. Putin acknowledged recently that he was “a KGB officer under the roof, as we say,” noting that the rector knew about it.

Putin told a journalist, Natalya Nikiforova, that he did not move up higher in the KGB ranks because he did not want to move his family to Moscow. “I have two small children and old parents,” he said. “They are over 80, and we all live together. They survived the blockade during the war. How could I take them from the place they were born in? I could not abandon them.”

Putin also said then that he wanted to write a dissertation “on a subject I always knew and understood, I mean international private law.” Musin said Putin came to him to make preparations for the dissertation but then dropped it when he got reacquainted with one of his old law professors, Anatoly Sobchak.

Sobchak, a leader in the first wave of democratic reformers in the Gorbachev years, was elected chairman of the Soviet-era Leningrad council. Putin quit the KGB, at the rank of lieutenant colonel, to work as Sobchak’s aide. In 1991, the city governance system was changed, and Sobchak became St. Petersburg’s first post-Soviet elected mayor.

Sobchak, like many of the early democrats, “was not prepared to govern,” recalled journalist Sergei Shelin of New Times magazine. Sobchak constantly collided with members of the newly renamed legislature, the city Duma. Putin often was dispatched to repair relations. “Sobchak often asked Putin to go to the deputies,” recalled Mikhail Amosov, a member of the Yabloko party. “Sobchak had bad relations with the lawmakers. There were always frictions. Sobchak always wanted to put them in their place; he treated them like an enemy force.”

Putin quietly played a key role for Sobchak at the moment of the 1991 Soviet coup attempt. Sobchak, in Moscow at that moment, vowed to defend Yeltsin and fight the coup, and took the risky step of flying back to his city to oppose the putsch. Putin, with good ties in the local security services, showed up at the airport with armed guards to protect Sobchak, who was potentially vulnerable as a leading democrat.

Vladimir Putin and former St. Petersburg Mayor Anatoly Sobchak talk during a 1997 economic conference in Russia. ( AP ) |

In the early days of the new Russia, Putin headed a committee to woo overseas companies to St. Petersburg. But the city primarily needed humanitarian aid. “There was no food in the city at all,” recalled Marina Salye, who was then a member of the legislature’s food committee. “There was no money. Barter was the only way – say, metals for potatoes and meat.”

St. Petersburg was a port and military city, and the state-owned shipbuilding and defense factories were stocked with precious metals. Salye said contracts were signed to trade metals for food, but she discovered the metals had been sold at discount prices, the food prices were inflated, and the food never arrived. Then it turned out that front companies had taken the profits and disappeared. Salye said she thinks Putin “was manipulating these contracts and was directly involved. But it hasn’t been proved.”

Salye confronted Putin, she recalled, but he brushed off her inquiries. “Everything is correct,” she said he told her. “You are just making up things.” Salye demanded an investigation, which was referred to a Moscow auditing commission and then dropped without explanation.

Putin, who speaks German, brought some companies to St. Petersburg, including German banks. A currency exchange was opened, and hotels were privatized. “All the work we did on privatization was supported by Putin, and not everyone was for it,” recalled Sergei Belyaev, a former deputy mayor and later a member of the Russian parliament. But St. Petersburg never lived up to Sobchak’s dream of becoming an international financial center. Moscow attracted far more foreign investment, while St. Petersburg lagged.

Putin’s influence grew under Sobchak, but he remained in the shadows. “In the Petersburg days, it was always other people in front of the television cameras,” said Igor Artemyev, leader of the Yabloko party. “Almost all the other vice mayors lined up next to the boss. Putin was always in the farthest corner.”

After Sobchak was defeated in 1996, Putin left for Moscow. There, for reasons which remain largely unexplained, he suddenly moved onto a remarkably fast career track. After first serving on the Kremlin staff, he became director of the Federal Security Service, the domestic successor to the KGB, in 1998, and later added duties as head of the Kremlin Security Council. He was picked for prime minister last August because he appears to have impressed Yeltsin’s inner circle and friendly tycoons, who were scrambling to find a premier and a potential Yeltsin successor.

During the same period, Putin apparently somehow found time to complete a postgraduate dissertation, which usually takes three years of study. He got a prestigious “candidate of science” degree, the equivalent of a PhD, from the Mining Institute in St. Petersburg in June 1997, a time when he was also working in the Kremlin.

Earlier, Putin had said he wanted to research international private law, but his 218-page dissertation was completely different. The title is “Strategic Planning of the Renewal of the Minerals-Raw Materials Base of the Region in Conditions of the Formation of Market Relations.” Much of the document is a discussion about the cost-effectiveness of building a port and roads in St. Petersburg, and offers little insight into Putin’s views of the market economy. The Mining Institute recently refused to show Putin’s thesis to a reporter. When a copy of a summary was found by the reporter in the institute’s library, officials snatched it away, saying it was private.

Mikhail Mednikov, a professor at the St. Petersburg Technical University, who was one of the “opponents” or reviewers at Putin’s oral defense of his dissertation, said, “The defense was brilliant. It’s a paper written by a market-oriented person.”

But while Putin has promised to keep Russia on a market path, his critics worry about his commitment to Russia’s young democracy. The institutions of a broad civil society – the press, political parties, free associations and others – are not yet well developed. The rule of law has not been well entrenched. And these weaknesses are, in part, a legacy of the Soviet police state of Putin’s early career, when the Communist Party had a monopoly on power.

In a long, private talk recently with the Moscow PEN writers group, Putin tried to evade the question of the KGB’s role in the Soviet system’s legacy of terror. Referring to the Stalin-era purges, in which millions were sent to prison camps and death, Putin said, according to a transcript, “Of course, one must not forget about the year 1937, but one must not keep alluding to only this experience, pretending that we do not need state security bodies [such as the KGB]. All the 17 years of my work are connected with this organization. It would be insincere for me to say that I don’t want to defend it.”

Putin then went on to offer a strangely oblique explanation for the Great Terror, which seemed to avoid blaming the KGB.

“The state security bodies should not be seen as an institution that works against society and the state; one needs to understand what makes them work against their own people. If one recollects those hard years connected with the activities of the security bodies, and the damage they brought to society, one must keep in mind what sort of society it was. But that was an entirely different country. That country produced such security bodies.”

He added, however, that if Russia will “treasure elements of civil society that we have got, our only gain over these years, then gradually we will be creating conditions under which those horrifying bodies of security will never be able to revive.”

Putin’s role in the blatantly misleading information issued by the government about the Chechnya offensive also has been criticized. His talent for creating legends has been evident in his explanations about the war. For example, Putin told the writers group that the military had been open with the news media, when the military has in fact hidden information about casualties, combat events, attacks on civilians and its goals and methods.

Felix Svetov, a writer who spent time in Stalin’s prison camps as a child and who lost his father in the purges, was present at the writers meeting. He said Putin’s comment “does not correspond with reality.” Putin is a typical KGB type, he added. “If the snow is falling, they will calmly tell you, the sun is shining.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login