Book Review by James Kwak July 5th, 2017 THE CHICKENSHIT CLUB Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute Executives By Jesse Eisinger 377 pp. Simon & Schuster. $28.

CLICK IMAGE ABOVE for direct link to NYT book review.

On April 27, 2010, Senator Carl Levin summoned the Goldman Sachs C.E.O. Lloyd Blankfein and his lieutenants before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations to answer allegations that the bank had misled investors prior to the 2008 financial crisis. Upon completing its investigation, Levin’s committee recommended that the Department of Justice open a criminal investigation into both Goldman’s business practices and the denials made by its executives before Congress.

Blankfein hired Reid Weingarten, a famous white-collar defense attorney who had once said of his work, “I feel like I’m in the French Revolution, defending the nobility against the howling mob.” Weingarten was a friend of Attorney General Eric Holder; his children went to Georgetown Day School with the children of Lanny Breuer, head of the criminal division of the D.O.J.

Breuer, who had spent much of the previous decade at the elite Washington law firm Covington & Burling, assigned the case to Dan Suleiman, a former Covington associate. Weingarten pestered Breuer, saying, “Close this …case, will ya?” In 2012, the Justice Department announced that it would take no further action against Goldman or Blankfein. That’s how the game is played. (A year later, Breuer and Suleiman both returned to Covington.)

Why was virtually no one prosecuted for causing the 2008 financial crisis, which devastated the global economy and cost the United States almost nine million jobs? Some people think the fix is in: Bankers control the government, so they can get away with anything. Others claim that the banks did nothing wrong to begin with — or, alternatively, that there was insufficient evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that anyone in particular committed a crime.

In this new book, the ProPublica reporter Jesse Eisinger tells a different story: Since the turn of the century, changes in the political landscape, the defense bar, the courts and most important the Justice Department have undermined both the ability and the resolve of America’s top prosecutors to go after corporations or their executives.

’Twas not always so. After Enron collapsed in 2001, federal prosecutors convicted the company’s accounting firm, Arthur Andersen, which surrendered its accounting license, as well as its three top executives. The former Enron C.E.O. Jeffrey Skilling is currently serving a 14-year prison sentence. By contrast, Goldman is still the world’s pre-eminent investment bank, and Lloyd Blankfein is still its C.E.O.

Perhaps it was too hard to prove that the bank’s actions — which included betting against structured financial products while it was selling them to clients — violated the letter of the criminal law. Eisinger does not address that question head-on, which may disappoint some readers. His point, however, is that the Justice Department’s prosecutors didn’t try very hard — and the few who did were reined in by their politically appointed bosses.

Andersen was already collapsing because it had shredded its own reputation, but the business community and the corporate defense bar played up the idea that an overzealous prosecution had put thousands of people out of work. Bigwig defense lawyers like Mary Jo White (future chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission) claimed that Andersen proved that the Justice Department should go easier on companies.

In the Obama administration, the idea that some companies are “too big to jail” was endorsed by both Breuer and Holder. Even the bank HSBC, which laundered hundreds of millions of dollars of drug money and illegally facilitated transactions with countries like Iran and Libya, got away with a fine.

This solicitous attitude toward corporations was part of a larger cultural shift in the business and legal world. Defending executives became an increasingly lucrative practice for elite law firms, which recruited star prosecutors from the Justice Department. Corporations accused of misconduct lawyered up, offering extensive internal investigations but erecting imposing defenses around individual executives. Banks cultivated plausible deniability, their internal oversight systems too feeble to pin responsibility on any individual; Goldman executives used the abbreviation LDL — “let’s discuss live” — to hide their traces.

Prosecutors and regulators could either negotiate a modest settlement and declare victory or take on the daunting task of bringing actual people to trial — with the significant risk of losing. “A symbiotic relationship developed between Big Law and the Department of Justice,” Eisinger writes. Corporations got off paying symbolic penalties, defense firms raked in huge fees, and prosecutors earned P.R. victories — as long as everyone played along.

Increasingly, the prosecutors and the defense attorneys on opposite sides of the table are the same people, just at different points in their careers. Conducting a criminal investigation of an executive isn’t just risky; in addition to jeopardizing a future partnership at a prestigious law firm, perhaps most important, it incurs “social discomfort,” especially for the well-mannered overachievers who now populate the Justice Department. No one wants to be a class traitor, especially when the members of one’s class are such nice people.

In the eyes of the elite establishment, businesses are now job creators and pillars of the community. Executives who bend the rules are “good people who have done one bad thing,” in the words of one S.E.C. lawyer reluctant to bring charges against individuals. Prosecutors no longer punish lawbreakers, but instead make corporations promise to behave better in the future — in the end amounting to “at most a tollbooth on the bankster turnpike,” as the longtime S.E.C. attorney Jim Kidney lamented.

With its broad historical scope, Eisinger’s book lacks the juicy, infuriating details of “Chain of Title,” David Dayen’s chronicle of foreclosure fraud — another instance of white-collar crime that went largely unpunished. With its emphasis on institutions and incentives, it doesn’t serve up the red meat of Matt Taibbi’s “The Divide,” a stinging indictment of the justice system’s unequal treatment of corporate executives and street-level drug offenders. But for someone familiar with the political landscape of the contemporary United States, Eisinger’s account has the ring of truth.

After decades in which Wall Street masters of the universe were lionized in the media and popular culture, star investment bankers — rich, usually white men in nice suits — just don’t match the popular image of criminals. Democrats as well as Republicans cozied up to big business, outsourcing the Treasury Department to Wall Street and the Justice Department to corporate law firms. Even after the financial system collapsed, the Obama administration’s priority was to bail out the megabanks — to “foam the runway,” in Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner’s words. The Justice Department became increasingly staffed by intelligent, status-seeking, conformist graduates of the nation’s top law schools — all of whom had friends on Wall Street and in the defense bar.

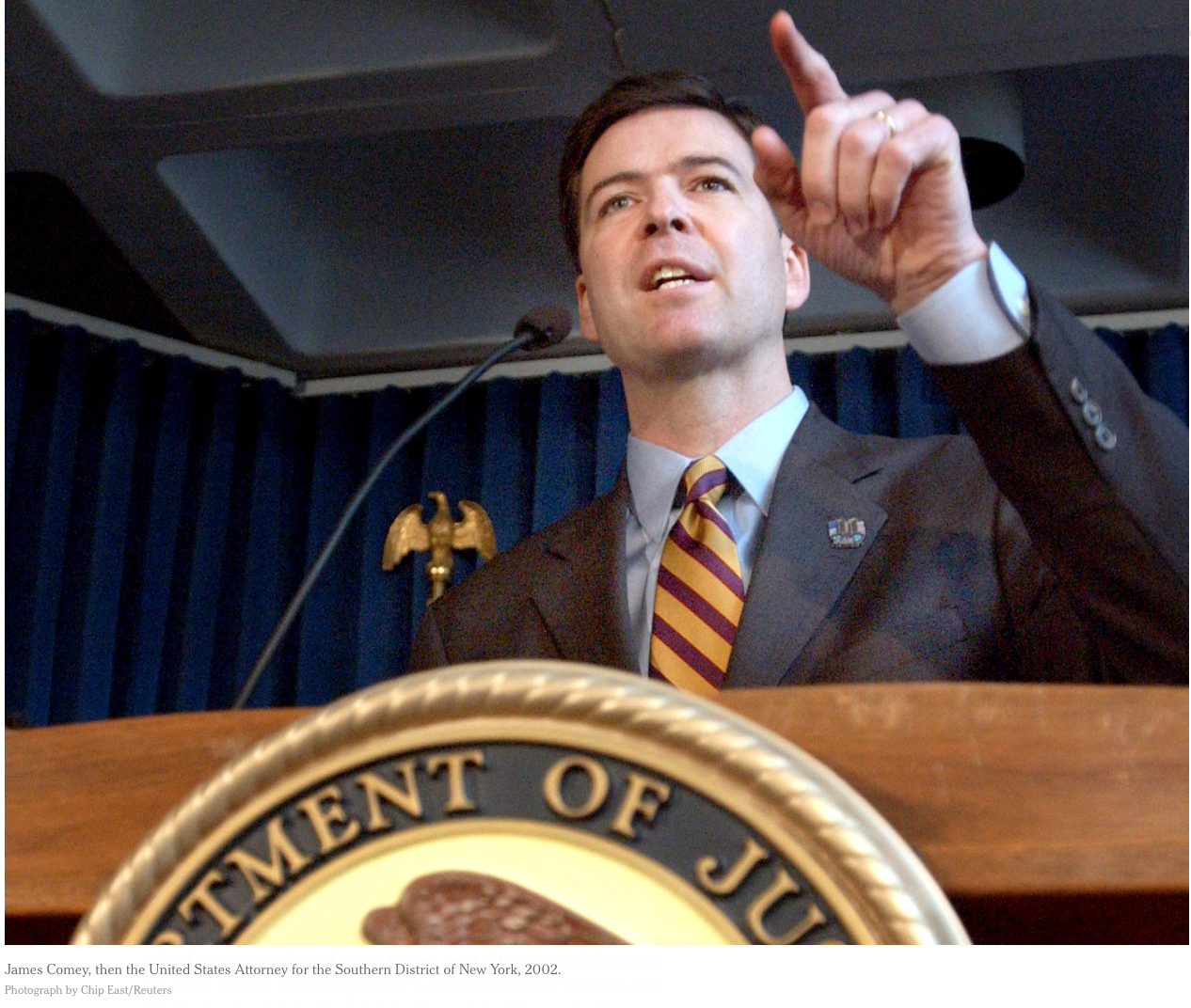

In that environment, the easy choice was to play along, strike a deal with an impressive-sounding fine (to be absorbed by shareholders) that held no one responsible, and avoid risking an acquittal or a hung jury. (The book’s title comes from then-U.S. Attorney James Comey’s name for prosecutors who had never lost a trial.) Corruption can take many forms — not just bags of cash under the table, but a creeping rot that saps our collective motivation to pursue the cause of justice. As Upton Sinclair might have written were he alive today: It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his résumé depends upon his not understanding it.

There’s just one problem. While the “unelected permanent governing class” may have been willing to look the other way when highly paid bankers wrecked the economy, many of the workers who lost their jobs and families who lost their homes were not. Outside the Beltway, the fact that the Wall Street titans who blew up the financial system suffered little more than slight reductions in their bonuses only reinforced the perception that the “system” is “rigged” — with the consequences we know only too well. Many people simply want to live in a world that is fair. As Eisinger shows, this one isn’t.

James Kwak is a professor at the University of Connecticut School of Law and the author of “Economism.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login