Once again in the young presidency of Donald J. Trump, women rallied against his administration on Wednesday, this time by skipping work, wearing red and refusing to spend money. But the protests were far smaller than the masses who turned the women’s marches on Jan. 21 into a phenomenon, keeping the question open of whether protesters’ fervor can be channeled into a sustained movement with demonstrable political results. CLICK IMAGE FOR LINK TO STORY.

In New York City, hundreds of people jammed into a Midtown block, and the Women’s March on Washington said 10 of its organizers were arrested there for blocking traffic. The municipal court in Providence, R.I., shut down because seven of the clerks and a deputy court administrator stayed home from work. Schools in Alexandria, Va.; Chapel Hill-Carrboro, N.C.; and Prince George’s County, Md., closed for the day because so many teachers stayed home.

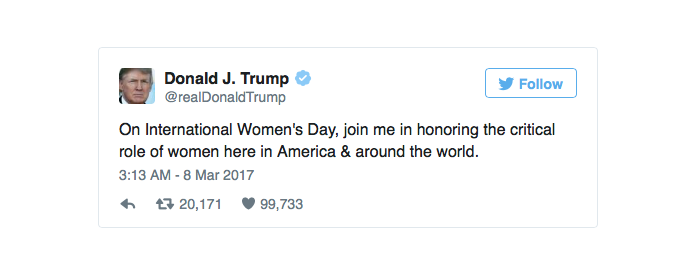

The strike was held on International Women’s Day, and President Trump weighed in early with a restrained statement, writing a message of respect on Twitter for women and the role they play in the economy.

Later, in Washington, women rallied near the White House to protest the “global gag rule” banning federal funding for any organization overseas that discusses abortion as a family planning option. But Rebecca Wood, 37, who brought her 4-year-old daughter, said her complaints were broader. “I used to list so many things on a sign,” she said. “Now I have so many concerns, I just have a sign that says ‘RESIST.’”

It was always unlikely that a general strike, labeled “A Day Without a Woman,” would produce the same turnout as the post-inauguration marches. The strike lacked the marches’ momentum coming off the election, as well as their virality and visuals, like the photogenic pink “pussy hats” that many attendees wore. It is also hard to tally participation or impact because employers could not provide counts of how many women stayed home, and retail figures are not yet available to show whether women stopped spending money.

Some questioned the decision to call a strike at all. “In order to work, a general strike has to actually stop something from functioning,” said Todd Gitlin, a former president of Students for a Democratic Society who has written about political movements. “Anywhere it hasn’t done that can’t be counted as a success. It plays to your inner audience, not your outer audience.”

The strike’s leaders tried to manage expectations from the start. “The object for us isn’t that we hope to shut the whole economy down,” said Linda Sarsour, a co-chairwoman of the event who was arrested. “We see this as an opportunity to introduce women to different tactics of activism. Our goal is not to have the same numbers as the march.”

Critics have charged that the call for a strike reinforces one of the central tensions of this next wave of women’s activism: the gap between white, privileged women and minority, lower-paid women, who may not be able to afford a day off from work and could lose their jobs. Ms. Sarsour said that was why organizers deliberately offered a menu of ways to participate if women could not strike.

Janna Pea, a spokeswoman for the Women’s March, said that as of Tuesday, more than 30,000 people had registered their intent to participate, most of them in the blue states of New York and California.

One-day mass protests are valuable displays of political muscle and hard for politicians to ignore. Ultimately, Mr. Gitlin said, protesters must be wooed into the harder, more dogged work of continuous organizing and political participation that changes policies or wins elections.

There is some anecdotal evidence that this is beginning to take place. Ms. Sarsour said the march had produced an instant national database that is being used to match first-time protesters with organizational tools for activism.

Women, deployed by Planned Parenthood and other groups, were at the forefront of recent town hall meetings, confronting members of Congress about plans to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

More than 5,000 small-group meetings were held across the country last month, at the urging of the women’s march organizers, to form networks to push for political change in local communities. A national call-in convened by a similar network of women’s groups to encourage protests about health care drew 58,000 people in mid-February.

And many women are joining forces with a bevy of groups that have sprung up since the election to foster activism with technological tools, such as Indivisible, which provides a template for influencing members of Congress; SwingLeft, which identifies nearby swing districts and offers opportunities to volunteer; and countless more.

Many women marked the day in personal ways. Kellee Stemac, in the conservative city of Plano, Tex., said she had misgivings about asking women to strike, so she planned to wear red and spend money only at women-owned businesses.

A few dozen red-clad demonstrators turned out at a downtown plaza in Lafayette, Ind. Gloria Goings, 63, a retired nurse and first-time protester, said she had come because of “the injustice that women deal with — like jobs, everyday life.”

But attendance was only a fraction of what it was at the march in January, when hundreds took to Lafayette’s streets, and the impact on business Wednesday seemed limited.

The same was true in Phoenix. Kristy King, who helped organize the January march, said that the strike was a welcome show of solidarity, but that low-income women might not have been able to attend. “I could think of better ways of spending my time,” she said a few hours after she decided to join Wednesday’s protest at the Arizona State Capitol.

In Denver, Theresa Newsom, a teacher, said she had driven 90 minutes from Colorado Springs for her first political march, noting proudly that she had a male substitute in her classroom.

In Silicon Valley, where women have often battled hostile workplaces, many companies were eager to demonstrate their support. Uber, which has been weathering a storm caused by a female engineer’s complaint about sexual harassment, sent a memo to employees last week saying they were welcome to participate in the strike, said MoMo Zhou, a spokeswoman for the company. Because Uber offers unlimited vacation time, no one will be docked pay.

Facebook — where Teresa Shook, a lawyer in Hawaii, first posted the idea of a march on Washington — is marking International Women’s Day with a 24-hour live feed of events.

Sarah Hofstetter, the chief executive of the advertising agency 360i, said that hundreds of the company’s 600 New York employees were participating in some way. Jezebel, a news site aimed at women, was run on Wednesday by men.

International Women’s Day was also observed around the world. Women in Tbilisi, Georgia, demonstrated under a symbolic “glass ceiling” to illustrate limitations on women’s advancement. Tens of thousands of Polish women held protests. In India, where a toilet is still an aspiration for many women, Prime Minister Narendra Modi presided over a celebration of women who had worked hard to secure this basic item for their families.

But not everyone had the option to protest. Jo Sorrentino, a 28-year-old arborist from Oakland, Calif., posted on Facebook that she would have lost a day’s pay. On an hourly wage of $21.50, she said, “I can’t afford it.”

An earlier version of a photo caption accompanying this article misstated a message printed on scarves. It is “A Day Without a Woman,” not “A Day Without Women.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login