by: Gary Silverman

During the first decade of this century, Donald Trump began doing business with an unlikely partner — Bayrock, a New York property developer founded only a few years before by a Soviet-born newcomer to the US named Tevfik Arif

Yet when Mr Trump testified under oath in 2011 about his relationship with Mr Arif’s company, he confessed that he found his partners puzzling. Mr Trump said he knew what they did. But he said he was unsure of exactly who they were.

“I don’t know who owns Bayrock,” Mr Trump said. “I never really understood who owned Bayrock. I know they’re a developer that’s done quite a bit of work. But I don’t know how they have their ownership broken down.”

Mr Trump’s Bayrock blind spot gains significance in the context of this year’s presidential race. Mr Trump has taken a stance on Russia that is at odds with US political orthodoxy — praising President Vladimir Putin’s leadership skills and saying he would consider lifting sanctions imposed on Russia after its 2014 annexation of the Crimean peninsula in Ukraine. Critics have asked whether Mr Trump’s business interests might be colouring his policies.

Mr Trump has responded by saying he has “zero investments in Russia”. But that is not the whole story. In recent years, Mr Trump has worked diligently to forge alliances with Russia-connected businessmen that would position him to profit from capital pouring out of the former states of the Soviet Union, and to seek opportunities in those locales. If no deals followed, as was often the case, it was not for a lack of trying.

Elusive figures

Mr Trump’s Bayrock connection reveals the risks he took along the way. By his own admission, he agreed to serve as the public face of a murky business. Court records in cases involving Bayrock only underscore the company’s complexity. When Winston Churchill called Russia “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma,” he might as well have been talking about Mr Arif’s operation.

Bayrock’s founder boasts a résumé reflecting the topsy-turvy business world that took shape following the fall of communism. Born in Kazakhstan, Mr Arif, 63, worked in the food and hospitality unit of the Soviet commerce and trade ministry before operating an export-import business, building hotels in Turkey and heading to New York as the century began to develop property in the borough of Brooklyn.

There were bumps along the way. In 2010, Mr Arif was arrested in Turkey on charges he helped arrange an orgy on a yacht that had once belonged to the country’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. In 2012, the charges were dropped, a company spokeswoman says. Today, Mr Arif is believed to be living in Turkey. His spokeswoman said he was the “sole owner” of Bayrock during the time it did business with Mr Trump. She declined to provide details, citing litigation and confidentiality agreements.

Mr Arif’s right-hand man, Felix Sater, came to Bayrock from the criminal underworld — and left the group with a reputation as a valued government asset. Born in Russia in 1966 and raised in Brooklyn, Mr Sater was convicted of attacking a man in a Manhattan bar with a broken margarita glass in 1991, opening facial wounds that required 110 stitches. After going to prison, he admitted taking part in a $40m securities fraud that involved several members of New York Mafia families.

Mr Sater pleaded guilty to one count of racketeering in the Wall Street case in 1998 as part of an agreement with US prosecutors to serve as a confidential informant in investigations involving organised crime and national security.

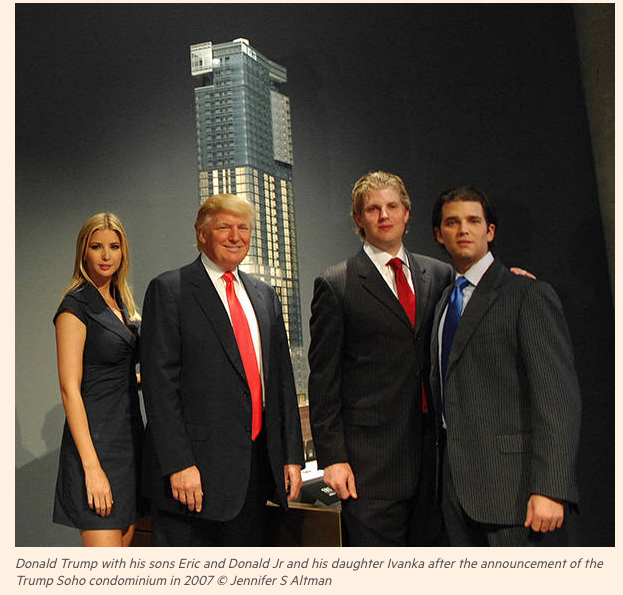

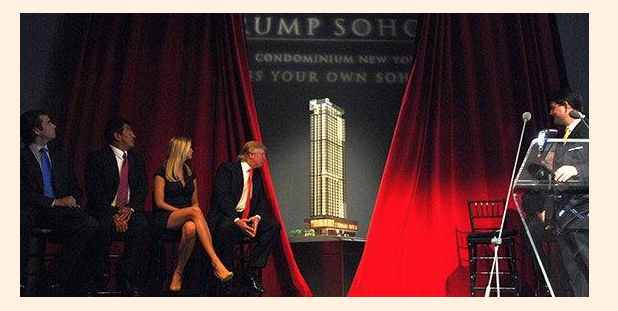

The extent of his criminal past came to light when The New York Times profiled him in 2007, only months after he and Mr Arif had joined Mr Trump and his older children Donald Jr, Ivanka and Eric at the launch party for Trump SoHo. By 2008, Mr Sater had left Bayrock. In 2015, during hearings on her nomination as US attorney-general, Loretta Lynch credited Mr Sater with providing information “crucial to national security” while working as an operative.

In the private sector, Mr Sater remained an elusive figure, sometimes spelling his name as Satter and routinely carrying business cards with different titles so he could use whichever one fitted the occasion. Generally, the more interested Mr Sater was in an opportunity, the higher his rank became.

“It was different monikers . . . managing member, managing something. Bottom line: I was probably No 2 man in the company,” Mr Sater said in a 2010 deposition. “[Mr Arif] was the boss. He was the boss of all bosses.”

“It was different monikers . . . managing member, managing something. Bottom line: I was probably No 2 man in the company,” Mr Sater said in a 2010 deposition. “[Mr Arif] was the boss. He was the boss of all bosses.”

Another level of complication at Bayrock came in the form of foreign partners. In 2007, before the Trump SoHo launch, Bayrock struck a complex deal under which it essentially traded anticipated profits from Trump SoHo and other projects for $50m in financing from the FL Group, an Icelandic company that collapsed the following year along with much of the island nation’s economy. (Iceland subsequently sought rescue financing from Russia, but several months of talks between the countries on a loan failed to produce an agreement.)

Mr Trump, Donald Jr and Ivanka were informed of the FL deal in advance and signed letters acknowledging the receipt of the information. Inside Bayrock’s ranks, however, the FL financing triggered a rebellion.

The finance director, Jody Kriss, filed racketeering lawsuits alleging the deal cheated him and other employees while diverting money to people outside the company. Among the beneficiaries, he alleged, was a man convicted in the same securities fraud as Mr Sater: Salvatore Lauria. The suit alleges Bayrock paid Mr Lauria $1.5m between 2004 and 2008. Bayrock has filed a motion describing the matter as “an ordinary employment dispute” and has asked a federal judge to dismiss the suit.

The importance of FL Group to Bayrock was highlighted in a company marketing brochure that described it as one of the developer’s two “strategic partners”. The other was Alexander Mashkevich, the Kazakh billionaire who is a major shareholder in ENRC, a miner that was delisted from the London Stock Exchange in 2013 amid corruption allegations. Alan Garten, general counsel of the Trump Organisation, said Mr Trump had no involvement with either Mr Mashkevich or the FL Group.

‘Very international’

Mr Trump turned to Bayrock as his career path changed. By the 2000s, the property developer and casino owner with ready access to the capital markets and the biggest New York banks was no more. A series of corporate bankruptcies had limited his financing options. Mr Trump had become an entertainer who portrayed a tycoon on television and licensed his name to businesses looking for a brand, leading to fee-making opportunities as disparate as Trump University and Trump Vodka.

“I’m in a unique position,” he said in a 2013 deposition. “I built up a great name and the name is something people like and it [licensing] has been very successful . . . Most of the jobs are good.”

The property variation on the licensing theme was the Trump “signature” development — a project built to Trump specifications by non-Trumps. Trump SoHo was an example.

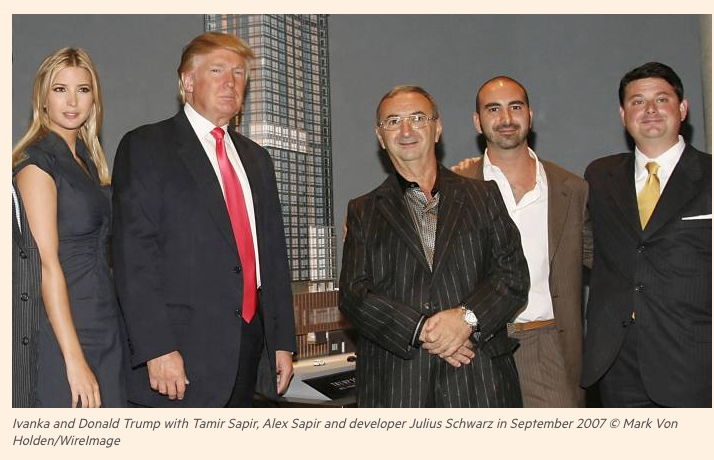

When he discussed the condo-hotel on The Apprentice, Mr Trump called it “my latest development.” But the actual developer — the entity that obtained financing and hired contractors — was a joint venture formed by Bayrock and another New York real estate firm with Soviet roots, the Sapir Organisation, founded by Tamir Sapir, a native of Georgia who died in 2014 aged 67.

Mr Trump testified in 2007 that he licensed his name to the Bayrock-Sapir team in return for 18 per cent of the profits. The Trump Organisation also managed the hotel in return for an annual fee of 3.75 per cent of gross revenues.

Mr Arif came to Mr Trump’s attention by following in his footsteps. After arriving in the US, Mr Arif began developing properties in the same area of Brooklyn where Mr Trump had worked beside his late father Fred, founder of the family’s real estate empire. Like Mr Trump, Mr Arif outgrew Brooklyn. He moved his company to Trump Tower — and soon found a new business partner.

“They took space in the building and that’s how Bayrock approached Trump,” says Mr Garten. “There was no prior relationship before them taking space.” In a 2013 deposition, Mr Trump described his tenants as taking the lead in their relationship. “Bayrock was interested in getting us into deals,” he said, adding that “it could have been Felix Sater” who brought him the idea for what became the Trump International Hotel & Tower project in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Mr Trump and Mr Sater took their act on the road, meeting the Colorado press in 2005 while making an unsuccessful bid to redevelop Union Station in Denver. The Rocky Mountain News described Mr Sater as Mr Trump’s “associate” and called Bayrock a member of Mr Trump’s “team”.

Mr Trump said he and Mr Arif discussed potential deals in cities including Istanbul, Warsaw, Kiev and Moscow. Usually, Mr Arif would call Mr Trump. Other times, he popped into Mr Trump’s office — including once when Mr Trump remembered him bringing two men from Russia.

“Mr Arif had the contacts — he’s very international,” Mr Trump said.

Members of the Trump family bragged about their connections to Russian money as they tried to drum up interest in Trump SoHo. As the US property market wobbled, the message from the Trump marketing machine was clear: the Russians were coming.

“Russians make up a pretty disproportionate cross-section of a lot of our assets, say in Dubai, and certainly with our project in SoHo,” Donald Trump Jr told eTurboNews in 2008. “We see a lot of money pouring in from Russia.”

A relationship fizzles

In the end, it was not enough. Sales at Trump SoHo proved disappointing. Some disgruntled buyers sued, accusing project representatives of inflating estimates of the number of units sold to stir demand. Trump SoHo settled without admitting wrongdoing, giving the unhappy customers 90 per cent of their deposits back.

Bayrock and Sapir were unable to pay back their creditors and Trump SoHo was sold at a foreclosure auction in 2014 to CIM Group, a real estate investor based in Los Angeles. A similar fate met Mr Trump’s licensing deal with Bayrock and another New York developer, Roy Stillman, in Fort Lauderdale. That luxury condominium project also passed into new hands at a foreclosure sale.

Mr Arif’s overseas leads failed to produce deals. In 2013, Mr Trump’s long search for a Moscow partner led him to talk with Aras Agalarov, a Russian real estate developer born in Azerbaijan, about building a local Trump Tower.

Bayrock eventually left New York’s Trump Tower. As its utility waned, Mr Trump’s memory of his Bayrock associates grew sketchier. In a 2007 testimony, Mr Trump recounted repeated interactions with the company and said, “I dealt mostly with Tevfik.”

By 2011, Mr Trump said, “I don’t know him very well, Mr Arif. I’ve met him a couple of times.” By 2013, Mr Trump said, “He [Mr Arif] was there at Bayrock a long time ago. I don’t know if he still is. I don’t think so.”

Mr Sater briefly came back to the Trump fold in 2010. Given a chance by the Trump Organisation to help look for deals, Mr Sater handed out business cards identifying himself as a senior adviser to Mr Trump. No transactions resulted and Mr Sater left without being paid, Mr Garten said.

Testifying in 2013, Mr Trump expressed sympathy for Mr Sater and discussed his personal history in detail before pronouncing him a virtual stranger.

“He got into trouble because he got into a bar-room fight, which a lot of people do. I don’t because I don’t drink,” Mr Trump said. “But I don’t think he was connected to the Mafia and I don’t know him very well.” Mr Trump added: “If he were sitting in the room right now, I really wouldn’t know what he looked like.”

In a statement issued by his lawyer, Mr Sater said last week that he “fully supports Donald Trump and believes he will make the best president of this

century”.

This article has been updated to correct the characterisation of Russia’s involvement with Iceland during the island nation’s financial crisis. The two countries held talks over several months on a loan but failed to reach an agreement.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login