EMMA GREY ELLIS BUSINESS DATE OF PUBLICATION: 01.11.17. 7:09 PM.

BUSINESS DATE OF PUBLICATION: 01.11.17. 7:09 PM.

PRESIDENT-ELECT DONALD TRUMP campaigned on his business acumen. His image as a hyper-successful, tough-talking real estate mogul is crucial to his appeal—whether it’s true or not. Still, concerns that Trump’s sprawling network of business entanglements creates an equally expansive web of conflicts of interest have dogged the Trump camp for many months. Because all the business experience in the world won’t make you a successful president if you’re hamstrung by your past dealings at every turn.

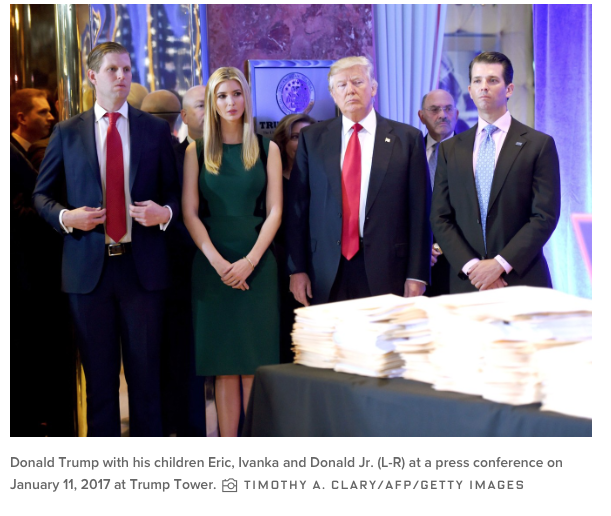

So at a press conference on Wednesday, Trump attempted to assuage those concerns. The problem? The plan Trump outlined—essentially, turning the business over to his adult sons Eric and Donald Jr.—hasn’t resolved any conflicts of interest at all. According to legal experts and business ethicists, the plan is unacceptable: the trust Trump proposes isn’t blind, and it leaves him a bad position with everyone from banks to foreign diplomats.

Let’s start with the basics: that pesky blind trust. Typically, presidents either divest themselves of their business assets (selling them off is an easy way to do it), or put them in a blind trust controlled by an impartial third party with no business-related contact with the sitting president. Trump hasn’t sold off a single taco bowl, so he’s opting for the trust. Sort of. “Turning over his business dealing to his two sons does not constitute a blind trust,” says W. Michael Hoffman, founding executive director of the W. Michael Hoffman Center for Business Ethics at Bentley University. “Anybody with a brain would understand that.”

The risk of throwing aside the blind trust custom is just as obvious: with Trump still more or less at the wheel, his business entanglements become political leverage. “When you’re on both sides of the deal your loyalty cannot be assessed,” says Alicia Plerhoples, a business lawyer at Georgetown Law. Which puts Trump’s (large) debts held by numerous banks in a different light: “There is the potential that he might be more reluctant to enforce our laws upon those banks, and the domestic implications of that alone should be enough to give us pause,” Plerhoples says.

When you add in that considerable portions of Trump’s debts are held by foreign banks such as Deutsche Bank, the impacts of their leverage take on an exciting new texture: Trump’s multinational business presence will become part of international relations calculus. Stories of his hotels becoming ways for foreign diplomats attempt to curry favor with the president-elect have been making the rounds since November. And the lack of blind trust magnifies an issue that already would have been sticky. Trump’s promise, meanwhile, to send the profits from foreign governments’ visits straight to the US Treasury misses the heart of the matter: this isn’t only about money, it’s also about power and influence.

Swamp Ethics

But Trump already knew people weren’t on board with this not-so-blind trust. So at today’s press conference, Trump and Sheri Dillon, a lawyer in his employ, outlined some additional ethical safeguards: the Trump men promise not to discuss business, and the Trump team will appoint an ethics advisor and a chief compliance counsel to make sure that the Trump Organization stays on the straight and narrow.

“Hiring your own ethics advisor is just a nonstarter in terms of conflicts of interest,” says Plerhoples. “The Trump Organization can hire and fire that person at will, and that person knows it.” For real: their solution to the conflict of interest problem just adds a layer of conflict of interest. Which creates a total lack of transparency and no real tools for anyone to check in on the Trump Organization’s dealings, aboveboard or otherwise.

And the thing is, it doesn’t actually make a difference whether Trump attempts to benefit from his newfound political position or not. “Even with the best intentions in the whole wide world, situations like the one Donald Trump has described lead to unconscious bias,” says Philip Nichols, a professor of legal studies and business ethics at University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business (Trump’s alma mater).

He may not be scheming when he brags about his hotels in front of a foreign diplomat, but the impact is the same either way. And perception is really what matters here: “Let’s say the administration gives a concession to China,” says Nichols. “Even if its made on the basis of some future deal, it’s going to look like the administration didn’t want to upset a party that holds a lot of leverage over the Trump Organization.” No way that doesn’t lead to some other country crying foul.

Which isn’t to say that kind of thing would go over well nationally, either. And while there are some potential fixes—Plerhoples and Hoffman both pointed out that the US Office of Government Ethics have made their careers on this kind of thing, and could be the un-conflicted third party this plan so desperately needs—this situation looks irretrievably sketchy.

Trump’s plan is far too anemic to fix that, which may cost more than divesting his assets would have. “It looks a lot like the swamp that people wanted to drain,” Nichols says. “He waged a uniquely aggressive campaign about issues of integrity, honesty, and trust. The position he volunteered for requires sacrifice on his part. Now would be a great time for him start.”

Go Back to Top. Skip To: Start of Article.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login