By Peter Elkin May 11th 2017

By Peter Elkin May 11th 2017

On Tuesday, when Donald Trump abruptly dismissed the F.B.I. director, James Comey, his Administration insisted that he was merely following the recommendation of his Attorney General and Deputy Attorney General, the two most senior officials in the Justice Department.

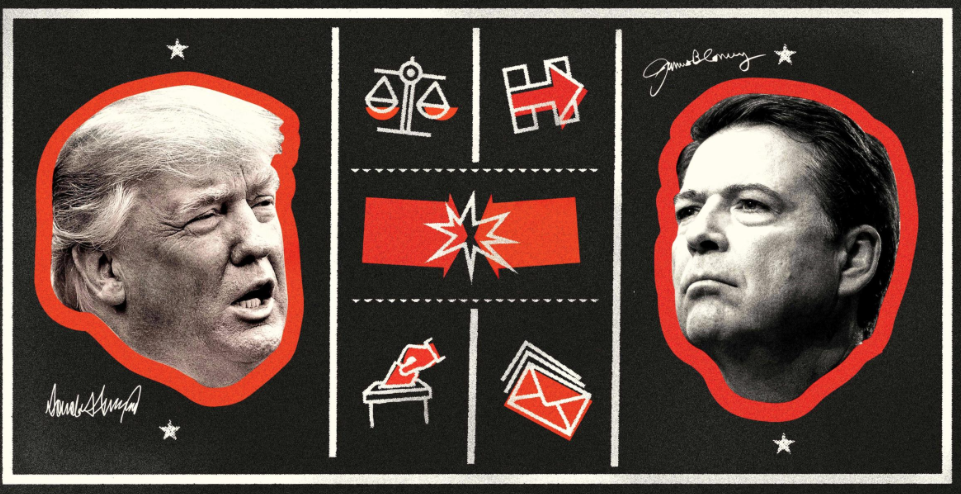

CLICK IMAGE for direct link to story.

In a three-page memorandum attached to Comey’s termination letter, the Deputy Attorney General, Rod J. Rosenstein, cited concern for the F.B.I.’s “reputation and credibility.” He said that the director had defied Justice Department policies and traditions and overstepped his authority in the way he handled the Hillary Clinton e-mail investigation.

This was a puzzling assertion from the Trump Administration, not least because Trump is widely acknowledged to have reaped the benefits of Comey’s actions on Election Day. After the F.B.I. director sent his letter to Congress, on October 28th, about the discovery of new Clinton e-mails and the Bureau’s plans to assess them, Trump praised Comey for his “guts” and called the news “bigger than Watergate.”

In the aftermath of Comey’s firing, Democrats and some Republicans in Congress have proposed a far more credible explanation for Trump’s action, accusing the President of trying to halt the F.B.I.’s investigation into Russian interference in the election and possible collusion with his campaign. Some of those legislators, as well as many critics in the press, have said that Trump has ignited a constitutional crisis, and they called for the appointment of an independent prosecutor to carry out the Russia investigation.

Comey’s dismissal came just as his Russia probe appeared to be widening. Just last week, the F.B.I. director went to Rosenstein, who had been in his job only for a few days, to ask for significantly more resources in order to accelerate the investigation, according to the Times. Tensions between the Trump Administration and Comey had been escalating already, and Trump’s fury over the F.B.I.’s Russia probe remained full-throated. On Monday, Trump tweeted that the inquiry was a “taxpayer funded charade.”

It is now clear that the aim of Rosenstein’s memo was simply to provide a pretext for Comey’s firing. White House officials may have thought it would be a persuasive rationale because Comey has come in for criticism from leaders of both political parties. Trump had been harboring a long list of grievances against the F.B.I. director, including his continued pursuit of the Russia probe.

On Thursday, Trump confirmed in an interview with NBC News’s Lester Holt that, even before he received the Deputy Attorney General’s memo, he had already made up his mind to dismiss Comey. In the end, Comey’s conspicuous independence—for so long, his greatest asset—proved his undoing, making him too grave a threat to Trump but also giving the President a plausible excuse to fire him.

Rosenstein’s memo does reflect genuine frustration inside the Justice Department about the F.B.I.’s handling of the Clinton e-mails, and betrays long-standing fissures between the two institutions, which are headquartered across from each other on Pennsylvania Avenue. Rosenstein, a Trump appointee who was previously the U.S. Attorney in Maryland, titled his memo “Restoring Public Confidence in the F.B.I.” In the wake of Comey’s ouster, the F.B.I.’s impartiality and competence remains an essential issue, making understanding what actually happened in the Clinton e-mail inquiry urgent as well.

Comey’s announcement about the discovery of the new Clinton e-mails did break with written and unwritten Justice Department guidelines against interfering with elections. Last week, during testimony before Congress, Comey cast the move as a singularly difficult decision and an act of principled self-sacrifice, driven by events far beyond his control. “I knew this would be disastrous for me personally,” he said. “But I thought this is the best way to protect these institutions that we care so much about.’’

A close examination, however, of the F.B.I.’s handling of the Clinton e-mails reveals a very different narrative, one that was not nearly so clear-cut or inevitable. It is one that places previously undisclosed judgments and misjudgments by the Bureau at the very heart of what unfolded.

“I could see two doors and they were both actions,” Comey recounted in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee. “One was labelled ‘speak’; the other was labelled ‘conceal.’ . . . I stared at ‘speak’ and ‘conceal.’ ‘Speak’ would be really bad. There’s an election in eleven days—lordy, that would be really bad. Concealing, in my view, would be catastrophic, not just to the F.B.I. but well beyond. And, honestly, as between really bad and catastrophic, I said to my team, ‘We got to walk into the world of really bad.’ I’ve got to tell Congress that we’re restarting this, not in some frivolous way—in a hugely significant way.”

But by the time Comey elected, on October 28th, to speak, rather than conceal, he and his senior aides had actually known for more than three weeks that agents sifting through files on a laptop belonging to the former congressman Anthony Weiner, as part of a sex-crimes investigation, had stumbled across e-mails sent by Clinton when she was Secretary of State. The agents had been unable, legally, to open the e-mails, because they fell outside the bounds of their investigation of Weiner.

F.B.I. officials kept the discovery to themselves. Without consulting or even informing the Justice Department lawyers who had worked on the e-mail inquiry, F.B.I. officials concluded that they lacked the evidence to seek a search warrant to examine the e-mails right away. Several legal experts and Justice Department officials I spoke to now say that this conclusion was unnecessarily cautious. F.B.I. officials also ruled out asking Weiner or his wife, Huma Abedin, one of Clinton’s closest aides, to allow access to the laptop—permission their lawyers told me they would have granted.

Instead, New York agents working the Weiner investigation, which centered on allegations of an explicit online relationship with a fifteen-year-old girl, were told to continue their search of his laptop as before but to take note of any additional Clinton e-mails they came across.

In the days that followed, investigators slowly sorted through the laptop’s contents, following standard protocols in a case that was anything but standard, and moving with surprisingly little dispatch to assess the significance of the e-mails.

After weeks of work, the agents concluded that the laptop contained thousands of Clinton messages, a fact they waited at least three more days to share with Comey. Finally, as Comey recounted before Congress last week, the F.B.I. director convened his top aides in his conference room at Bureau headquarters to weigh the political and institutional consequences of what to do next.

At this point, Comey and his deputies were venturing far beyond their typical purview as criminal investigators. Under normal circumstances, department policies discouraged public discussion of developments in ongoing cases of any kind; with the election fast approaching, there was the added sensitivity of avoiding even the perception of interference with the political process.

But F.B.I. officials worried that agents in New York who disliked Clinton would leak news of the e-mails’ existence. Like nearly everyone in Washington, senior F.B.I. officials assumed that Clinton would win the election, and were evaluating their options with that in mind. The prospect of oversight hearings, led by restive Republicans investigating an F.B.I. “coverup,” made everyone uneasy.

One more misjudgment informed Comey’s decision. F.B.I. officials estimated that it would take months to review the e-mails. Agents wound up completing their work in just a few days. (Most of the e-mails turned out to be duplicates of messages collected in the previous phase of the Clinton investigation.) Had F.B.I. officials known that the review could be completed before the election, Comey likely wouldn’t have said anything before examining the e-mails. Instead, he announced that nothing had changed in the Clinton case—on November 6th, just two days before the election, and after many millions had already cast their ballots in early voting.

The debate over Comey’s effect on the 2016 election and, now, his historic dismissal, is likely to persist for years. In the months since Donald Trump became the nation’s forty-fifth President, a number of media organizations—most recently, the Times—have scrutinized Comey’s handling of the Clinton e-mails. They have also examined Comey’s accompanying silence about the Bureau’s investigation of possible ties between the Trump campaign and Russia, an inquiry that began in July of 2016.

Clinton traces her loss directly to Comey; she asserted recently that if the election had been held on October 27th, “I would be your President.” Trump retorted, in a tweet, that the F.B.I. director was “the best thing that ever happened to Hillary Clinton in that he gave her a free pass for many bad deeds!’’

This account is based on interviews with dozens of participants in the events leading up to the election. They include current and former officials from the F.B.I. and the Justice Department who were eager to have their actions understood but unwilling to be quoted by name. Comey himself declined my requests for an interview. Back in early January, however, he replied politely to a written interview request, acknowledging that he was aware of my “ongoing work.” He wrote from an e-mail address whose whimsical name, he said, “the Russians may have a harder time guessing.”

Comey added a note of intrigue, suggesting that there were unappreciated complexities to the story that hadn’t yet become known: “You are right there is a clear story to tell—one that folks willing to actually listen will readily grasp—but I’m not ready to tell it just yet for a variety of reasons.”

During his testimony before Congress last week, Comey said that the possibility that he’d influenced the outcome of the Presidential election made him “mildly nauseous.” Previously, over two decades of public service, Comey had made independence from partisan politics the foundation of his political identity. Comey, who is fifty-six years old, had been the rarest of creatures in Washington: a Republican even Democrats could love.

A registered Republican for most of his adult life, Comey had made a point of telling a congressional committee last July that he was no longer affiliated with either party. (His distance from partisan politics extends to the voting booth; records show that Comey hasn’t voted in a primary or general election in the past decade.)

Comey rose to prominence through the Justice Department, first as a federal prosecutor in New York and Virginia, and then as the United States Attorney in Manhattan, and the Deputy Attorney General under President George W. Bush. From early on, colleagues say, Comey carefully cultivated a reputation for integrity and nonpartisanship. Until the events of the past year, it had always served him well. “He knew what was the right thing to do,” a former federal prosecutor who worked with Comey told me. “But he figured out how to execute it in a way that, whatever the result, Jim Comey would be protected. I say that respectfully. He has an exceptional gift for that.”

Comey liked to map out the ramifications of major decisions, often in lengthy meetings with deputies. At critical moments in his career, Comey showcased his independence—too eagerly, in the view of some who accuse him of “moral vanity.” “I think he has a bit of a God complex—that he’s the last honest man in Washington,” a former Justice Department official who has worked with him told me. “And I think that’s dangerous.”

Daniel Richman, a Columbia law professor and close friend of Comey who has served as his unofficial media surrogate, acknowledged Comey’s penchant for public righteousness. “He certainly does love the idea of being a protector of the Constitution,” Richman said. “The idea of doing messy stuff and taking your lumps in the press.” But Richman, who worked with Comey as a federal prosecutor in Manhattan, insisted that Comey’s motivations were sincere. “More than most people, he thinks that when it comes to making really difficult decisions, transparency and accountability have incredible value,” Richman said.

Among scores of people I interviewed, not even Comey’s harshest critics believe that he acted out of a desire to elect a Republican President. Comey built his reputation by taking on powerful figures of both parties. Most famously, while serving as acting Attorney General under George W. Bush, he’d raced to the hospital bedside of the ailing Attorney General, John Ashcroft, to confront Administration officials seeking Ashcroft’s reauthorization for a domestic-surveillance program that the Justice Department considered illegal.

Comey’s congressional testimony, in 2007, about the confrontation raised his public profile, earning him encomiums from both parties. In 2013, after Comey completed a seven-year interlude in the private sector, Barack Obama chose the Republican lawyer as the director of the F.B.I. “To know Jim Comey is also to know his fierce independence and his deep integrity,” the President declared, in a Rose Garden ceremony. The Senate confirmed him ninety-three to one.

The F.B.I. is a division of the United States Department of Justice, and its director reports to the Attorney General. But, from the start of his ten-year term at the F.B.I., Comey asserted a belief in the agency’s right to chart its own course. “The F.B.I. is in the executive branch,” Comey likes to say, “but not of the executive branch.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login